“I have always been unsatisfied with life as most people live it. Always I want to live more intensely and richly. Why muck and conceal one’s true longings and loves, when by speaking of them one might find someone to understand them, and by acting on them one might discover oneself? It is true that in the world such lack of reserve usually meets with hostility, misunderstanding, and scorn. Here in isolation I need not fear on that score, though the strangers I do encounter usually judge me wrongly. But I was never one to be content with less than the most from life and shall go on reaching, and having my soul defenseless to attacks. I seldom retaliate, for I perceive too well the ultimate futility.” – Everett Ruess, June 29, 1934

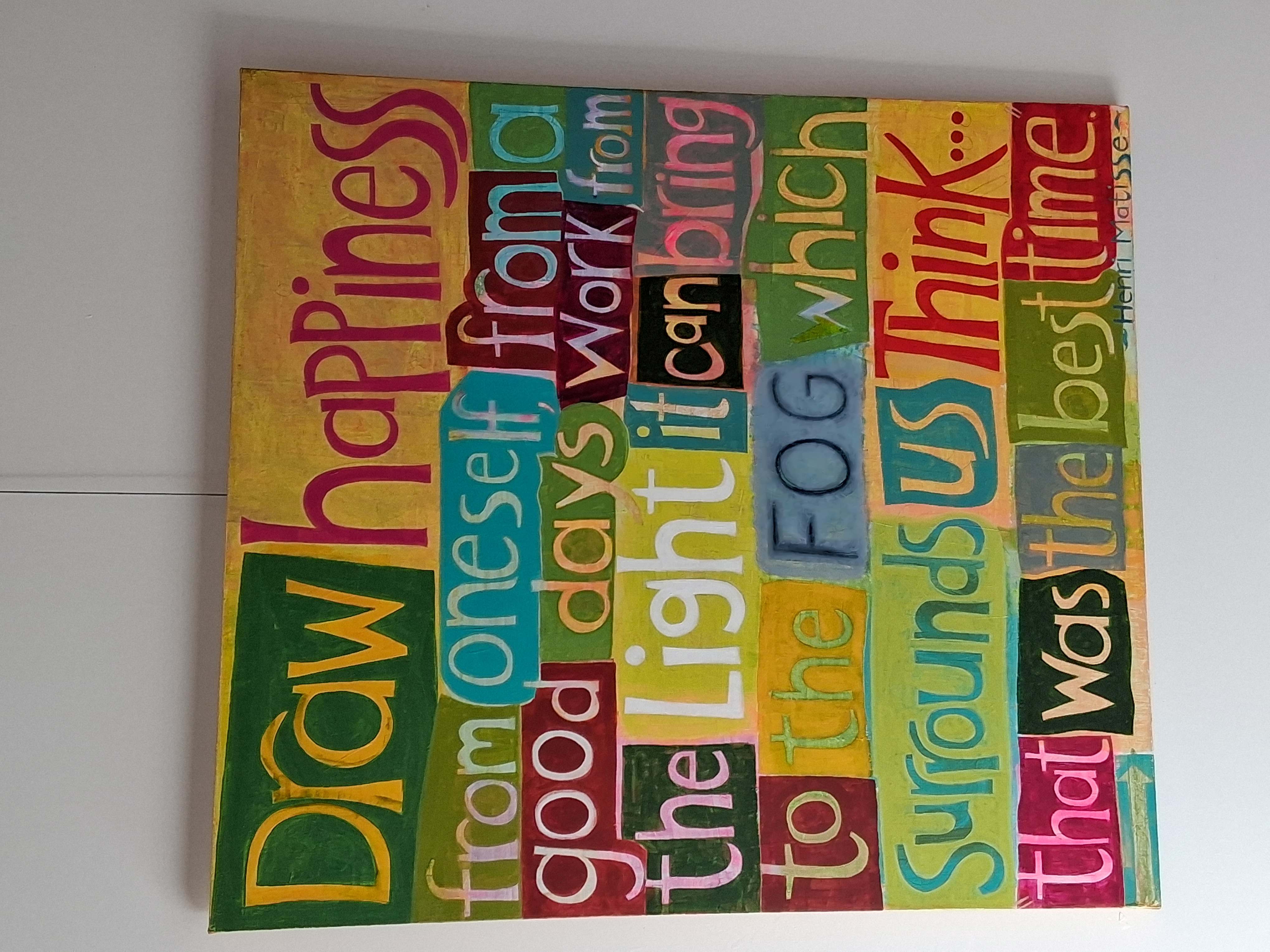

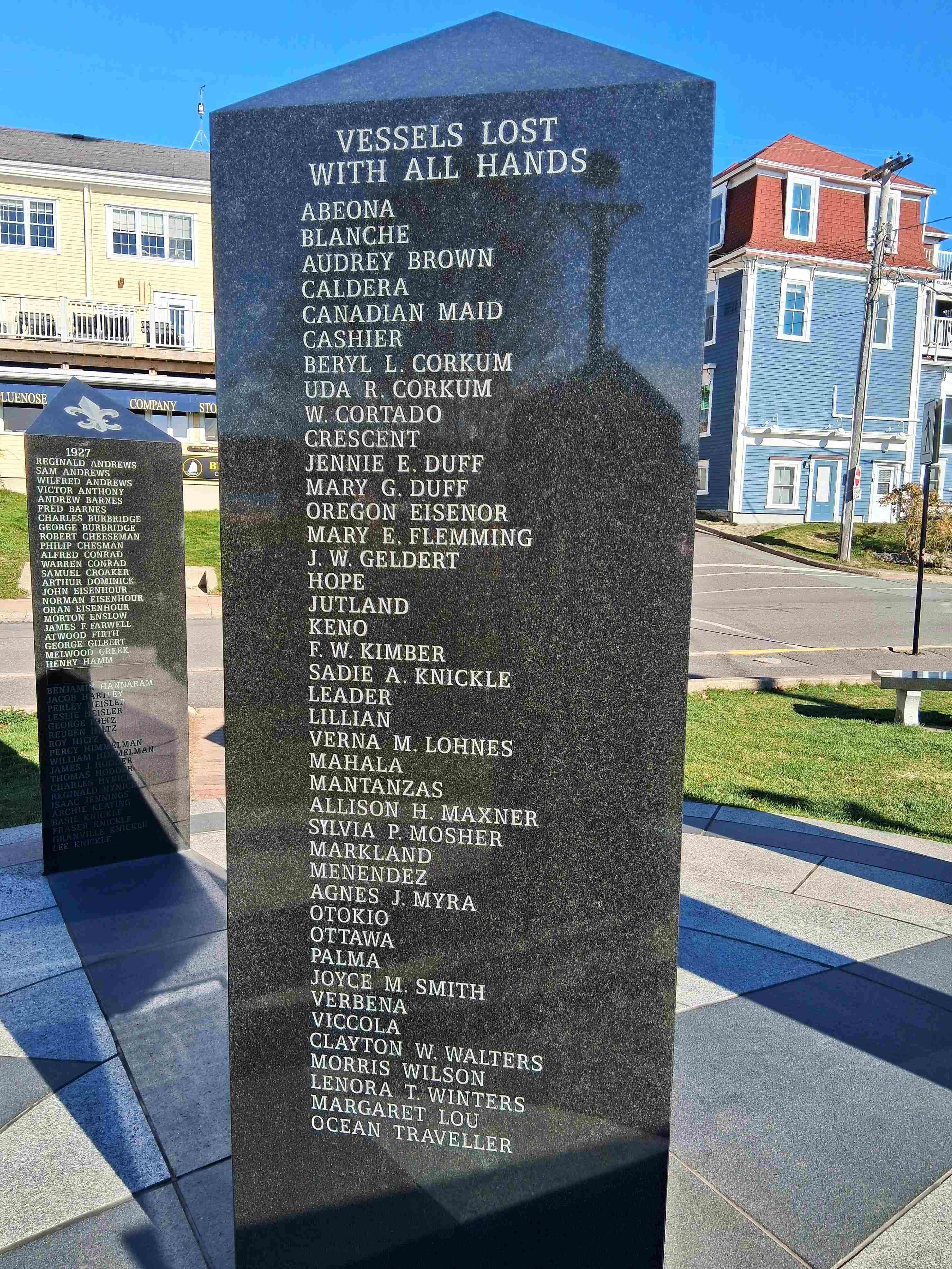

South Coast – Le Have and Lunenberg

The south shore of Nova Scotia is known for its picturesque small towns where fishing is still an important part of local economies, and for its historic buildings, artist galleries, restaurants, surfing beaches and resorts. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

On Sunday, Karl, Stephi and I had dinner at the historic White Point Inn. Beaches there and nearby attract surfers from as far away as Halifax when the waves are good.

I stayed in the Dockside Hotel in Lunenberg Sunday night with a room overlooking the harbor. Lunenberg was founded in 1753 by German immigrants and is known for its lobster fishery and its colorful historic Old Town which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Old Town streets rise steeply from the waterfront. Homes facing the harbor date from the 1700’s and 1800’s. There is no shortage of churches including St. John’s Anglican Church of Canada, founded along with the town in 1753, and built in the second half of the 18th century.

We lost Stan Rogers, Canadian singer songwriter, in 1983 at age 34, but not before he left us memorable songs from the Maritimes. A Stan Rogers music festival is held each year in Halifax in his honor.

Eastern Shore of N.S. – Herrick Cove Fire Station

Drove over to the east shore beaches north of Dartmouth where Karl surfs. Good waves but too much wind, so we stopped at the Rose & Rooster for coffee and brownies. Went a little further to the tiny village of Musquodoboit Harbour (“Musket-dob-it”) about 45 km. from Halifax to turn around and grab some fresh, locally grown produce at Uprooted, the local grocery store. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

On the way back to Halifax we stopped at the Herrick Cove Volunteer Fire Station where my son Karl is the Captain. The station has five salaried career firefighters who are on call 24-7 and twenty four volunteer firefighters who respond to calls as needed, when available.

Engine 60 is only 3~4 months old, cost approx. $750,000, and is the workhorse with the pump that feeds up to four hoses. The captain rides in the right front seat with a driver who does not leave the truck. Four additional firefighters ride in the crew cab where they gear up on the way to a fire. Engine 60 carries oxygen tanks for crew, fire hose, and specialty tools like chain saws, “jaws of life,” etc.

Tanker 60 carries approx. 1200 gal. of water, 1.5 km. of fire hose, and a two ladders, one of which is a 2-flight ladder that will support a fireman in full gear carrying a second person in the case of rescues from upper stories.

Bunks, bathrooms, kitchen, break room, gym, and Karl’s office are on the 2nd floor. There is a traditional fire pole for firefighters to descend quickly from the 2nd floor. You see the Canada flag along with one with the star, crescent, and red cross that is the Mi’maq flag of the indigenous people. Here’s a good place to mention that the Acadians have their own flag which is the French Tricolor with a yellow star in the upper left corner. I see it flown on homes of those who identify as Acadians.

Broken Bow Arch – Hole-In-The-Rock Road – The Mystery of Everett Ruess

In the Spring of 2023, I traveled to SE Utah and Grand Staircase- Escalante National Monument for the express purpose of traveling the Hole-In-The-Rock road south of Escalante, UT. The road leaves scenic Utah Highway 12 and traces the torturous route originally blazed by Mormon pioneer families in 1878-1879 on their way to found a new settlement on the San Juan River. Their short lived agricultural settlement became the small, present day outpost of Bluff, UT. My ultimate goal was to find and hike from the Willow Gulch trailhead down a sandstone canyon to Broken Bow Arch which had only recently emerged from the waters of Lake Powell after the reservoir level fell dramatically following years of drought. The trailhead is near the end of Hole-In-The-Rock road, some 50+ miles of rough road from where it begins, requiring 4WD and speeds of 15~25 mph. Thanks to an early start, I reached Willow Gulch by mid-morning in time to start the descent.

by David E. Miller, first published in 1962. His book is drawn from first person diaries and Mormon archives that document the hardships suffered and incredible endurance shown by the settlers who crossed the rocky plateaus and canyons in winter, on foot and in their covered wagons.

I did not realize it until today (!!) after reading Everett Ruess, A Vagabond for Beauty, edited by W. L. Rusho, but over much of the way to the trailhead I traveled the same route that Everett Ruess, a 20 year old Mormon artist, writer, explorer, and seeker of natural beauty, traveled on foot with his two burros on his way to to Davis Gulch in 1934 where he disappeared. The mystery endured until 2008 when a body discovered on nearby Comb Ridge was identified by DNA analysis as that of Ruess who had been murdered and his body buried to avoid discovery. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

At the start of the trail, I descended a very soft, red dirt bank to where the beginning of the gulch is a small drainage ditch. From there the natural drainage of the gulch deepens as it wends its way to the Escalante River, itself a tributary of the Colorado River.

Cottonwoods find enough water in the soil to establish themselves as the stream descends toward the river. The day I hiked the trail was overcast so the red sandstone color was subdued.

The trail to the arch alternately followed the dry stream bed, or led over the tops of high banks.

By the time I was in sight of the arch, a trickle of water was visible in the stream bed. To get to this point took several hours and I was cognizant of the time it would take me to retrace my route before nightfall on the shorter Spring days.

Duncans Cove, Nova Scotia

Karl’s house in Duncans Cove is about 20 minutes from Halifax and adjoins a Provincial Nature Reserve. Fox, bobcat, lynx, and deer are all native to the area and will occasionally cross the lawn. In the winter months he has the wood stove to supplement electric heat, which makes for a cozy living room. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Spruce trees are sparse on the thin soil and the vegetation is buffeted by strong winds most days of the year.

I hiked across the reserve to the lighthouse in 50 degree weather and then followed the rocks along the shoreline back to the house. Waves were modest today, October 30, but the effects of hurricane Melissa will bring heavy rain, strong winds, and high surf over the next two days, with the peak of the storm expected on Friday.

YESTERDAY, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 29

Karl and I rode the “Harbor Hopper,” a converted WW II amphibious vehicle that took us sightseeing around downtown Halifax and then, being amphibious, drove into the harbor so we could see the city from the water.

Trip Across Canada, 2025

I made this trip by train on VIA Rail from Vancouver, BC, to Halifax, NS, to visit my son Karl. For the first two nights, I stayed in the Samsun Hostel in downtown Vancouver. It was affordable, efficiently laid out with individual rooms ( 4 or 8 beds), plus shower rooms and bathrooms on all four floors. Everything was kept very clean by staff and guests. Free, all-you-can-eat breakfast was a healthy mix of fresh fruits, cereals, and bagels with butter and jam. Staff provided the food, but guests bussed and washed all their own plates, bowls, cups, etc. in the kitchen area at the back of the main floor. [All photos ![]() Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

Max Vollmer, Click on any image to enlarge]

I stayed in a 4-bed room and got a good night’s sleep both nights. Four metal lockers on rollers for personal belongings slid under the bottom bunks. Each bed also had a lamp and an outlet against its back wall to charge a phone, and a privacy curtain. While it was not supposed to happen, I ended up with a young woman for a roommate. Fortunately she wasn’t bothered.

I had a full day to explore a little of the downtown and to walk along the seawall to Stanley Park, a preserve with an old growth forest of cedars, firs and maples on a promontory west of the city center.

I boarded the Canadian, VIA Rail’s premier scenic run from Vancouver, BC, to Toronto, Ontario, on Sunday afternoon, 10/20. The entire train including my sleeper is vintage 1955, venerable but well maintained, with lots of solid stainless steel and aluminum trim and a few genuine leather details. I had my cabin, meant for two, to myself and appreciated the quiet comfort.

Meals are included in the sleeper fare and are served in the dining car by reservation. Tables for four meant that I met people from Germany, France, and Japan. The real surprise was how many of my fellow passengers, couples and singles, young and old, were Canadians (the majority) and many of them French speaking. Few were from the U.S. which was fine with me. Dinners included rack of lamb, beef tenderloin, and salmon, all excellent.

I took advantage of the surprisingly roomy shower room at one end of the sleeping car each morning at around 6:00 a.m. and then took a seat in the dome car to watch the day begin before breakfast.

Our longest stop on day two was in Jasper, BC, a jumping off place for Jasper National Park.

Jasper National Park does not disappoint and is the reason many people ride the Canadian.

The next morning dawned over the plains of Alberta and, yes, it is very flat. Saskatchewan is pretty much the same, perfect for growing wheat, barley, and oats for export.

By late afternoon on the third day, we were crossing the what’s know as the Canadian Shield, a region north of Lake Superior with the oldest exposed bedrock in the world. Something like 50 million years old. The climate is moderately wet and there were small bodies of water, like potholes, across the terrain all the way to Toronto, Ontario. From Toronto, I took a separate train to Montreal, Quebec, where I spent a day and two nights before boarding the VIA Rail Ocean to Halifax, NS.

The Ocean follows the St. Lawrence River through Quebec until it turns south into New Brunswick, the land of the Acadians. The story of Acadia and the 1755 Expulsion has not been forgotten locally. French and Acadian culture is still a big part of local life. Homes in small communities along the river were uniformly well maintained and small by U.S. standards.

When we turned south toward Halifax , we entered Mount Carleton Provincial Park and the forest was a mix of birch, eastern larch (bright yellow), spruce, pine, and fir.

My train ride ended in Halifax, three hours late which is typical of VIA Rail, where Karl picked me up. After eleven days traveling, I was more than ready for a hot shower and a long night’s sleep, a full four time zones away from Oregon. Karl’s house in Duncans Cove sits atop a rock face overlooking Halifax Harbor and is built on concrete footings set deep in solid granite and once held a shore battery to protect the harbor during WW I and WW II. Halifax and Dartmouth, NS, are on the horizon to the north.

Reward

Heceta Head on the Oregon Coast

Hayrake Table – In the Style of Sidney Barnsley

Sidney Barnsley (b.1865-d.1926), was an important and influential Arts and Crafts designer-maker who hand crafted furniture for his family and for clients. He had previously trained as an architect and worked in London before moving to the rural Cotswolds region of England, Pinbury Park and Sapperton in Gloucestershire.

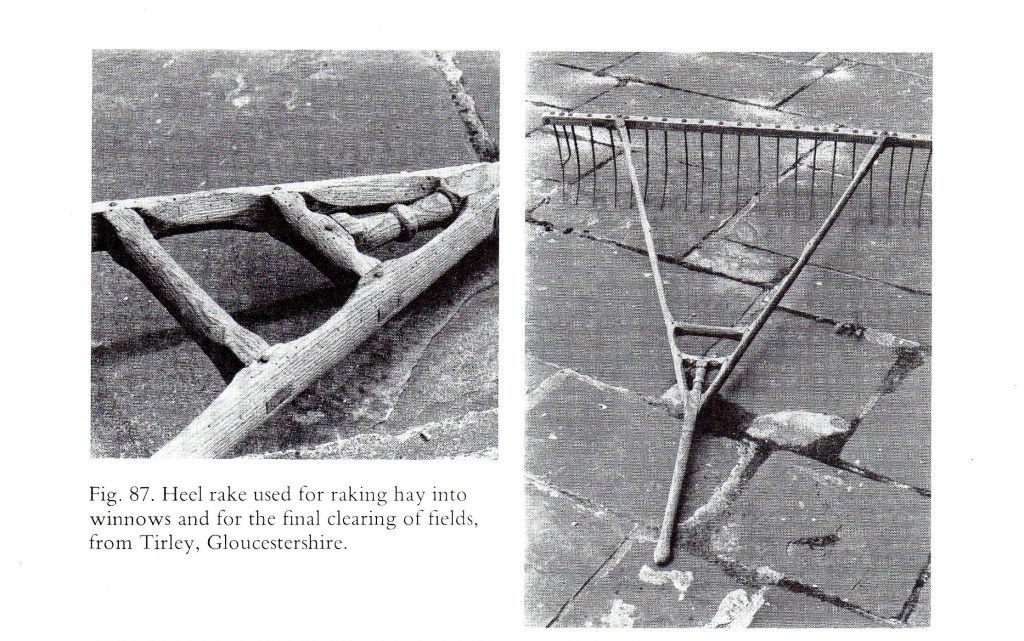

In early 2019, I decided to build an oak dinner table for myself with a leg set that incorporated a “hay rake” or “heel rake” stretcher, a feature that Barnsley had adapted for one of his tables from a traditional wooden rake used by farmers to rake hay in their fields into windrows. Below is a photo of one of these 18th~19th century rakes showing the joinery used to create the handle. It is a marvel of traditional, rural woodworking that is very strong but lightweight . . . a perfect example of form following function. [Click on any image to enlarge.]

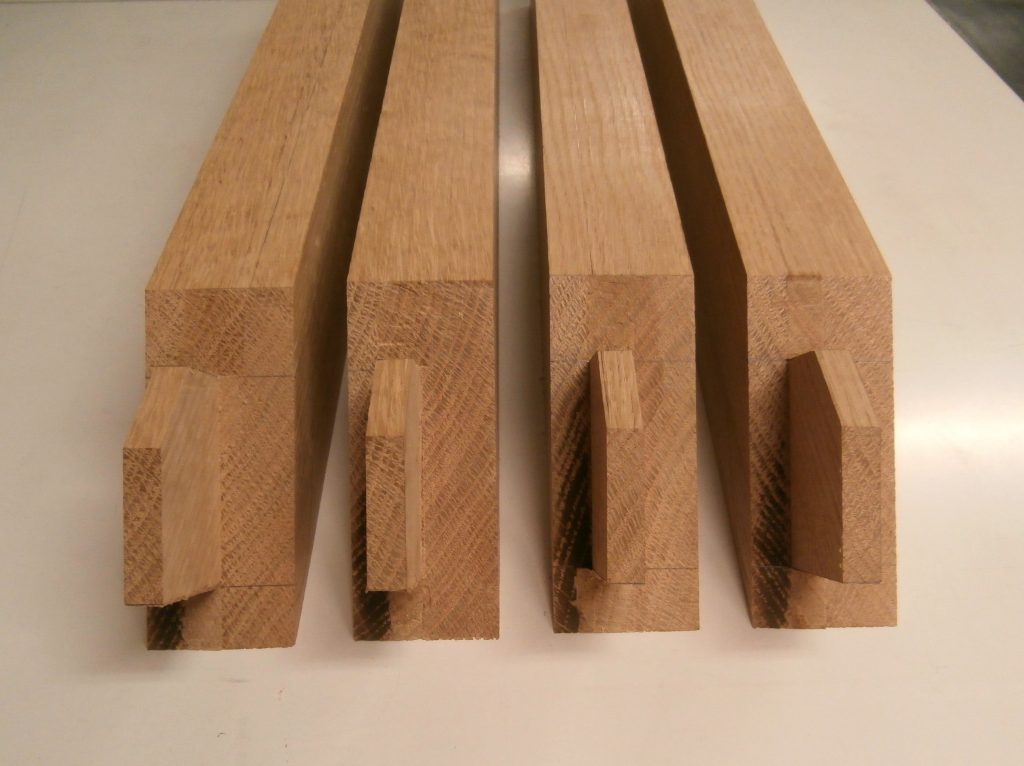

Barnsley used the essentials of the rake joinery to create the stretcher (see below) for his table, circa 1900. All three b&w photos are taken from Gimson and the Barnsleys by Mary Comino (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., 1980).

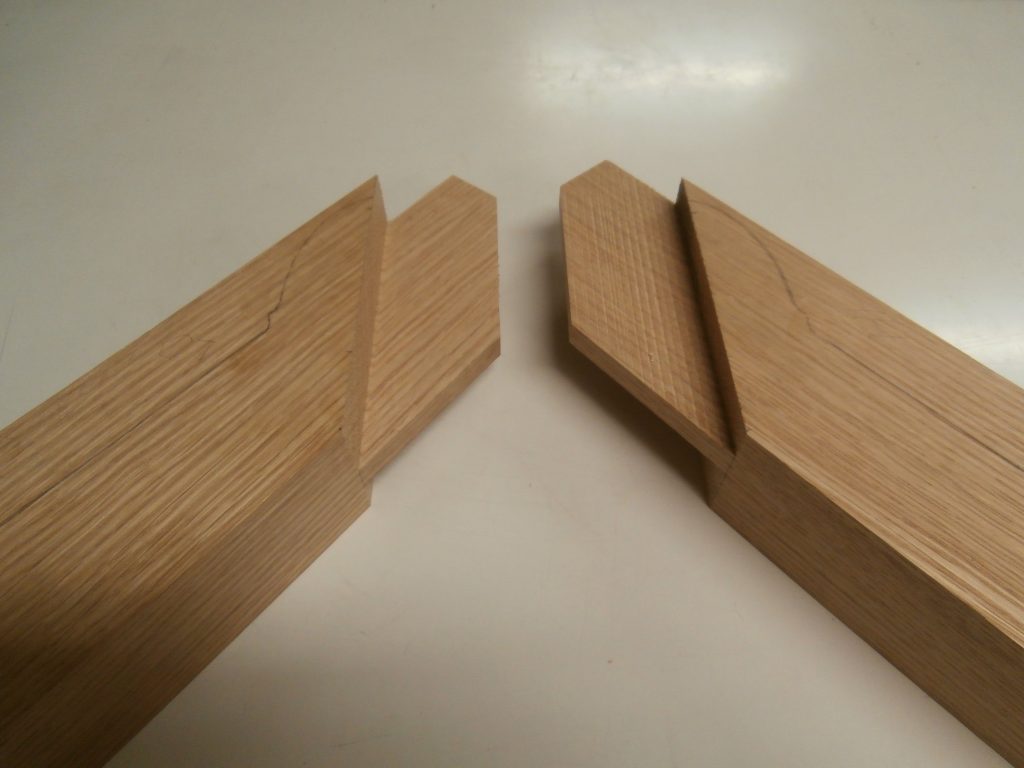

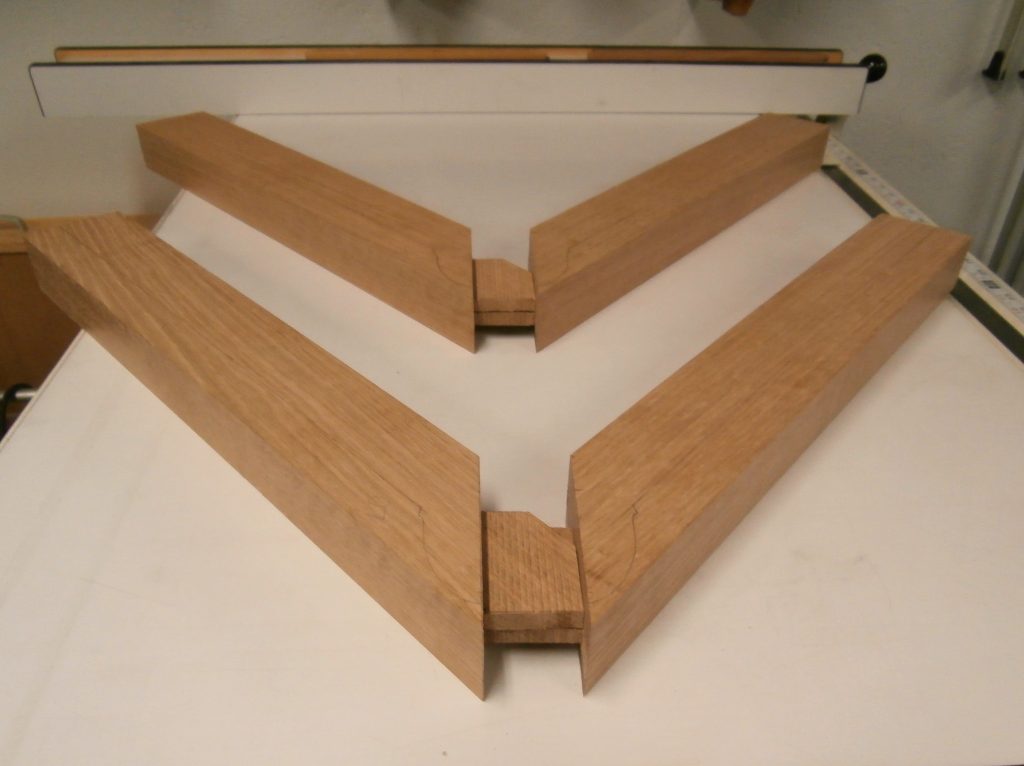

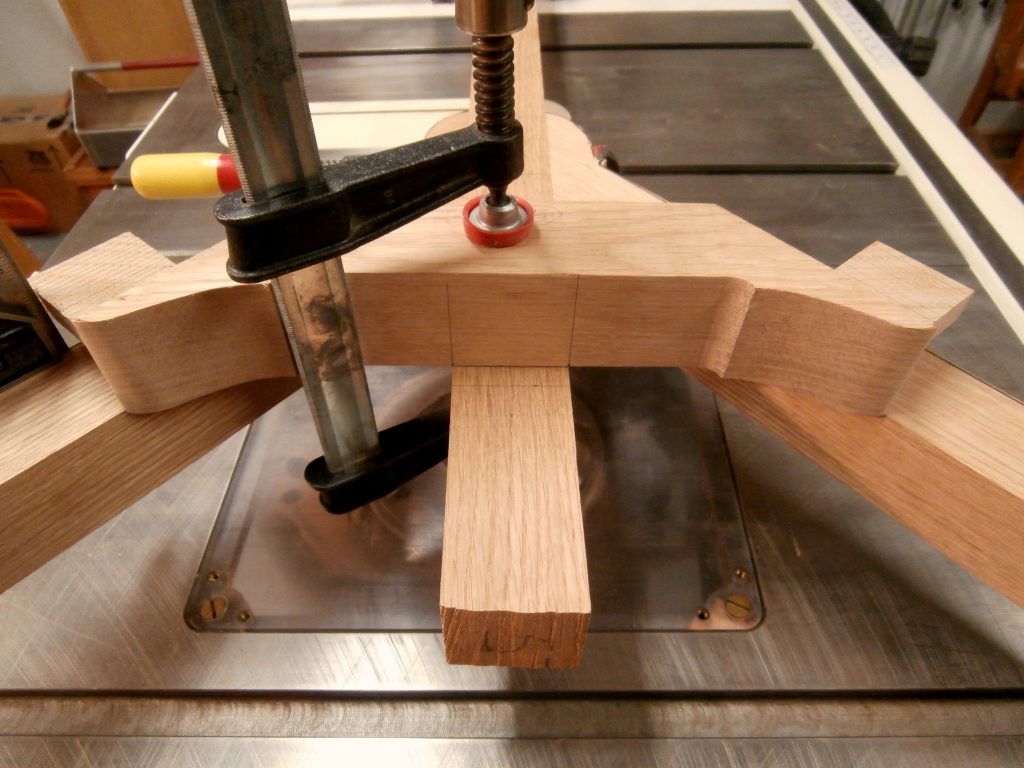

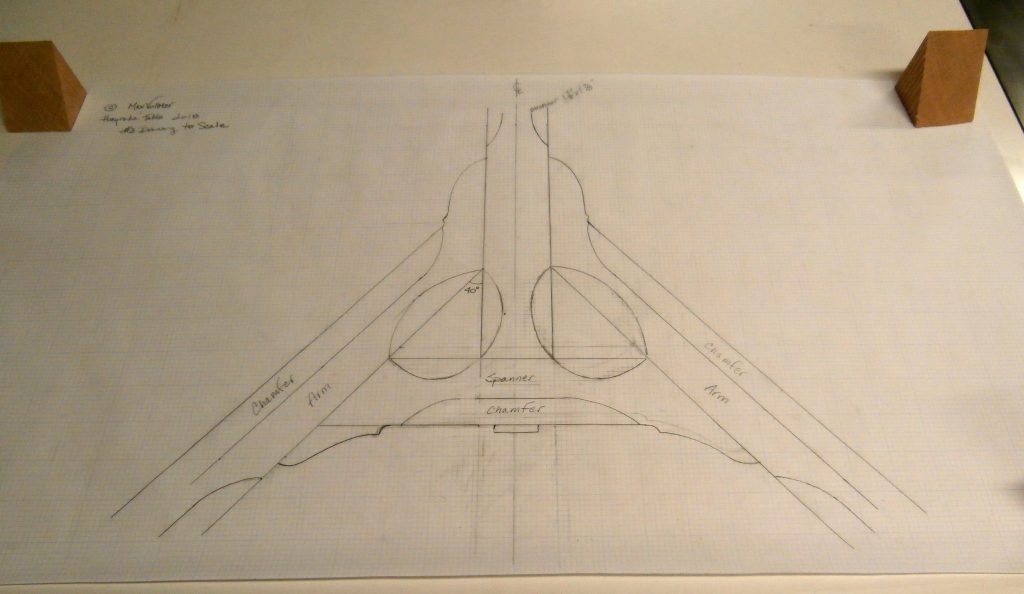

With no original drawings to go by, I made my own full size, scaled plans and set to work on the “Y” shaped joint only to find that my first effort was not going to be satisfactory. It ended up going in my wood stove. I revised the plans based on my experience and started over. [Click on any image to enlarge. All following photos ![]() Max Vollmer]

Max Vollmer]

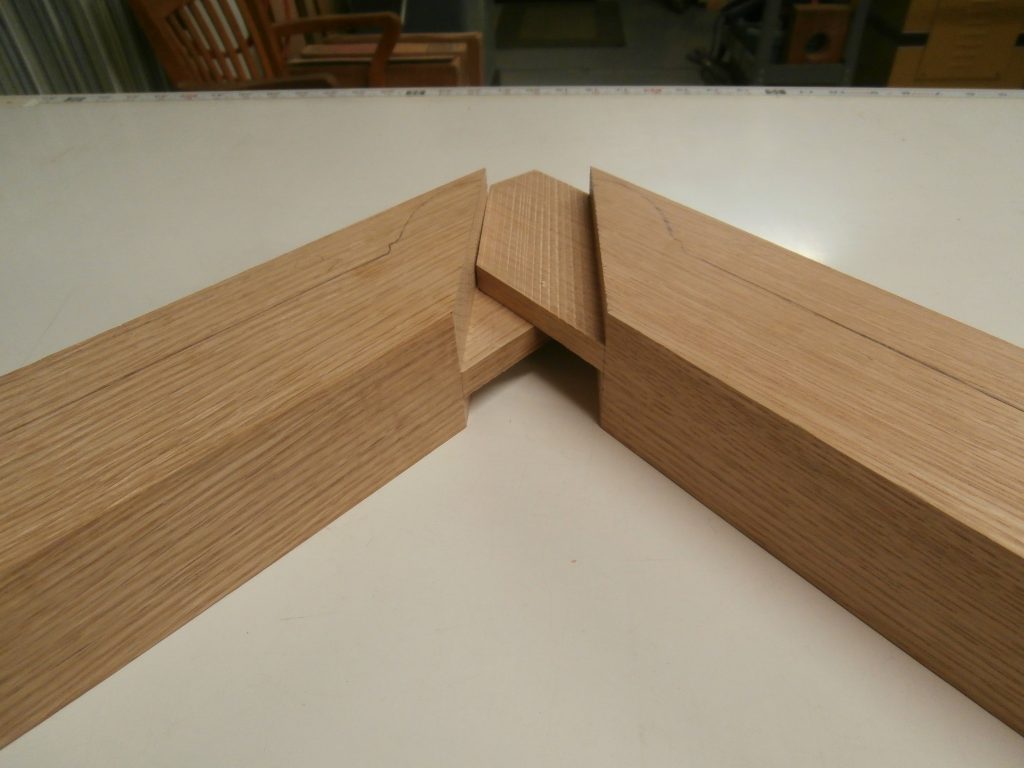

For aesthetic reasons I reduced the acute angle between the arms of the “Y” and the main, longitudinal stretcher from 45 degrees to 40 degrees. I used overlapping tenons on the arms where they intersect and join the main stretcher.

And, based on my first failed effort, I also redesigned the tenons on the “spanner” or brace that connects the two arms of the “Y.” This allowed me to cut “through” mortises in the arms that were perpendicular to the axis of the arms rather than mortises cut at a 40 degree angle. This way I could use straight tenons on the spanner. Not only was this redesign equally strong, it was much easier to cut the mortises. The following series of photos illustrate my approach. [Click on any image to enlarge, All photos ![]() Max Vollmer]

Max Vollmer]

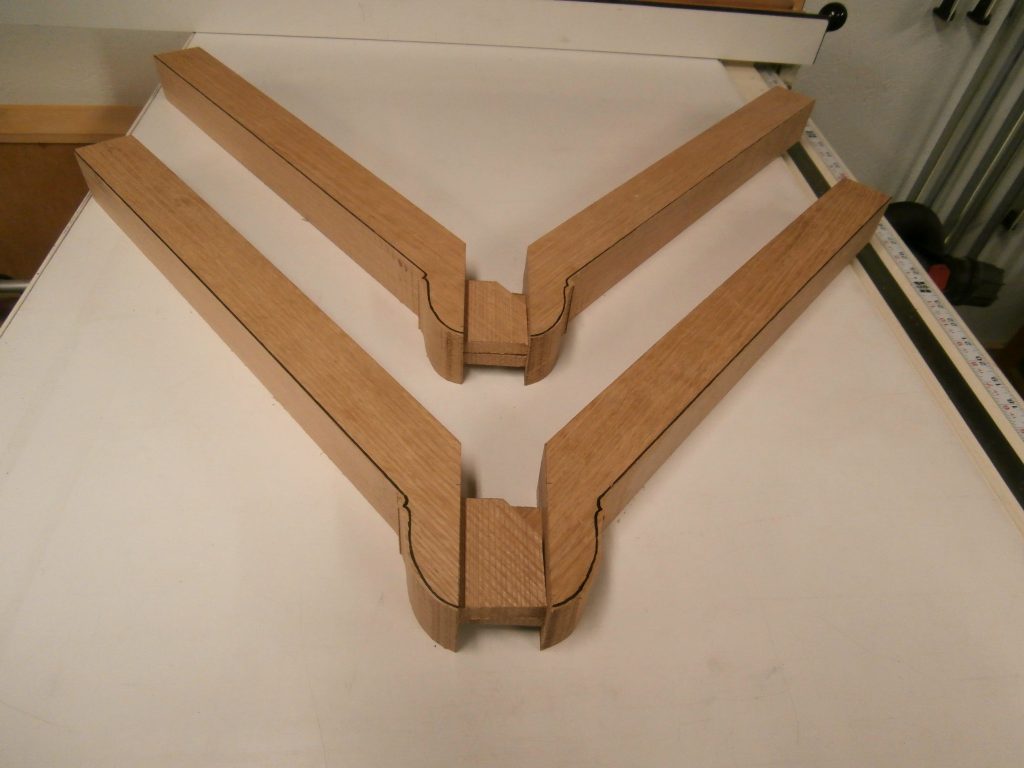

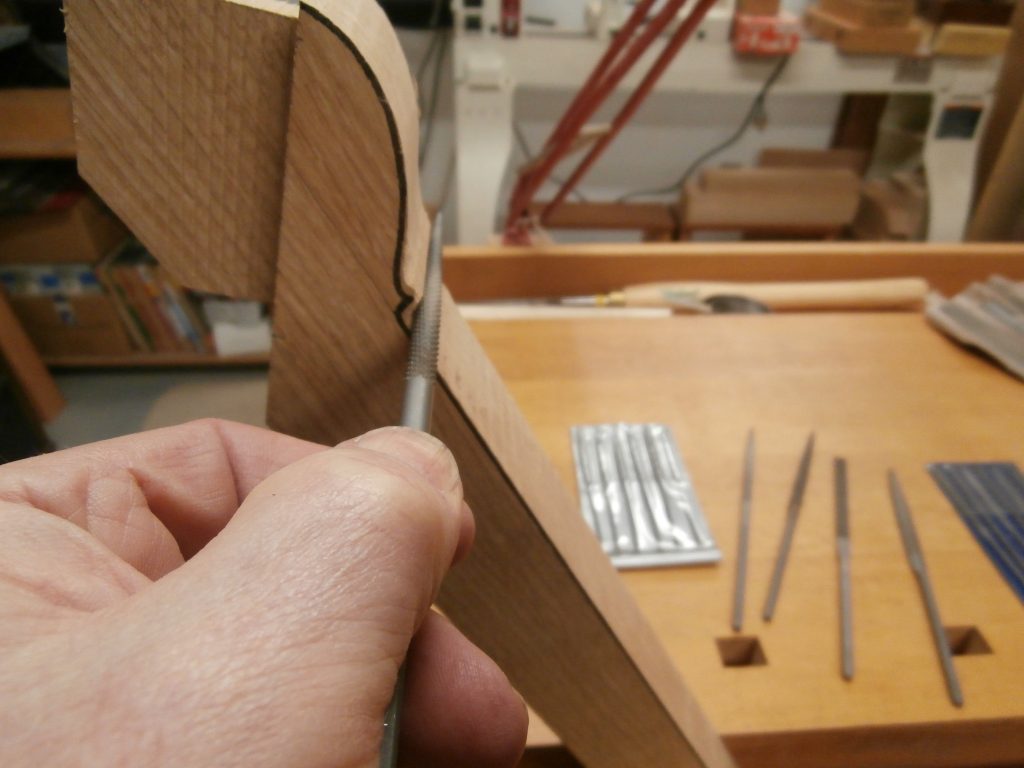

In the next stage, I used a felt tip pen to outline the reduced size of the arms with their curved detailing where the arms meet the long, center stretcher and then used the bandsaw to rough out the shapes. Following that I used an assortment of rasps, files, planes and sandpaper to refine the curved details. The following sequence takes you through the steps. This was a very time consuming process, and one that cannot be duplicated with finesse by any other means. This is what hand work is all about.

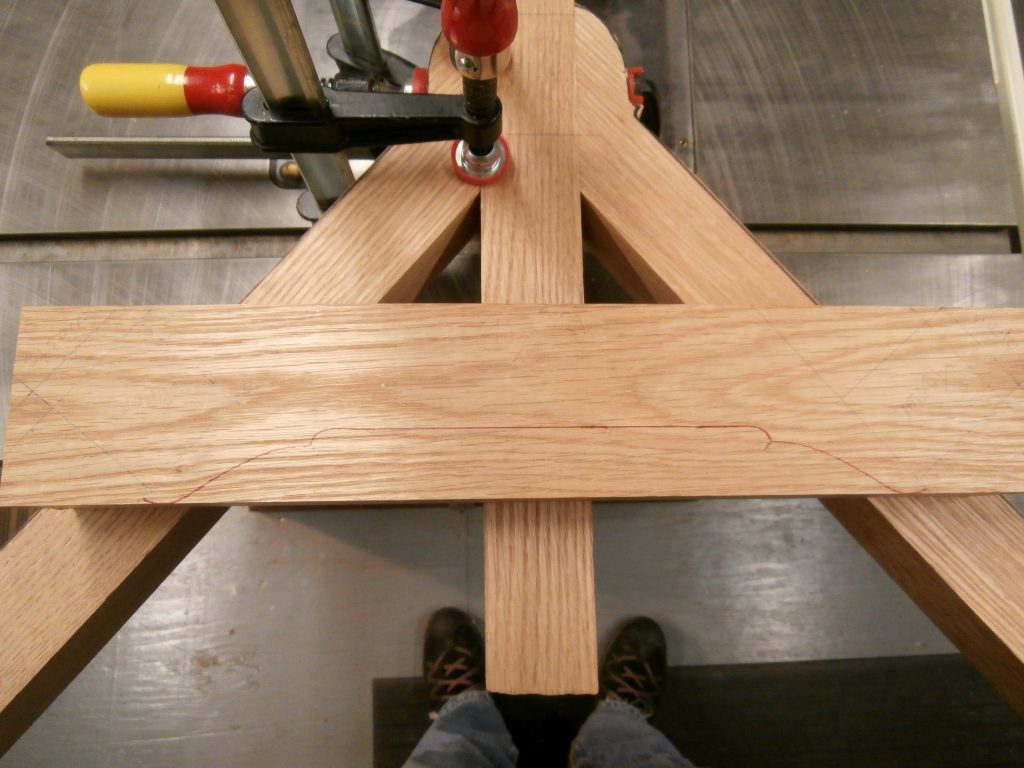

Next I dry fit the arms to the center stretcher to check my clearances. See below.

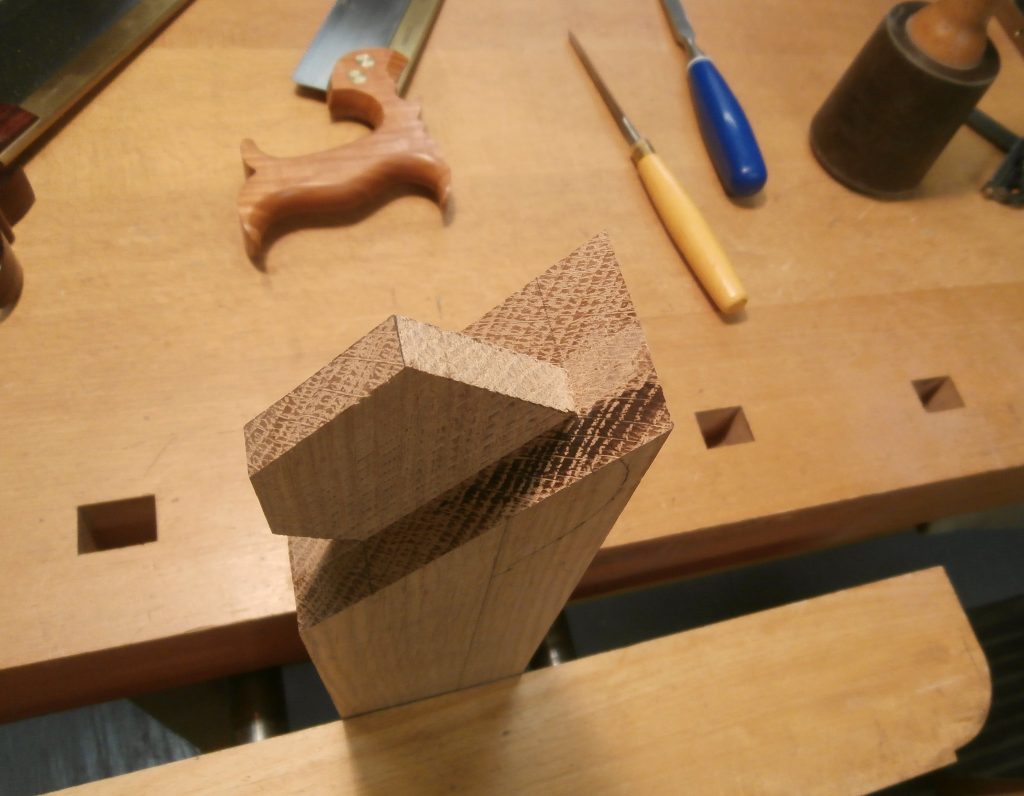

From there I consulted my full size, scaled plans for the spanner that connects the two arms and interlocks with the center stretcher. All measurements, markings, and cuts on the spanner must be extremely precise in order for all four pieces to fit together with tight joints. It is an added challenge to have all the through tenons emerge flawlessly where they are visible on the outside faces. Here is the sequence.

Assembled it looks like this.

The dry fit stretcher assembly is then marked with the location of all chamfers. The chamfers in the original hay rake do not compromise the strength of the rake, but they decrease the weight the farmer has to lift and pull for hours on end. In the table, weight is not a concern but the chamfers add immeasurably to the aesthetic appeal of the stretcher.

See below the full stretcher and leg set ready to go and then assembled. Barnsley chose to have the pegs that lock the tenons in their respective mortises visible from above. I put the pegs in from below so they do not show and therefore do not distract from the flow of the joinery.

Rounding out the table frame, I fit cross pieces to the tops of the legs and then installed two long, under-table supports that are joined to the cross pieces with dovetails. The result is a support structure that, barring fire or natural disaster, has an essentially unlimited lifespan (1,000 years?) if cared for. Here it is with finish and signed with my makers mark on a cross bar.

Here’s the table top. And, following that, the table in my house. Final dimensions are 68″ L x 38″ W x 31.5″ H. The table is compact, but the design of the hay rake stretcher and the canted legs allow for four chairs, across and end to end, and will accommodate four people comfortably for a meal.

I have the lumber to make a long, low, and narrow coffee table with the same hay rake stretcher design, to which I want to add wishbone struts under the table top for added complexity and interest, something Barnsley did in one of his tables. I just need a shop.

The Grand Gallery Pictographs – Canyonlands NP, Utah

In the late 1960’s, early 1970’s, I purchased a Sierra Club Ballantine book authored by the brothers, Renny and Terry Russell, titled On the Loose. It was comprised of their accounts and their photographs from explorations as young men in the wildlands of Utah. One picture they took and included in the book was of the “Grand Gallery” of ancient Native American pictographs in a small, separate and remote piece of Canyonlands National Park in Utah. The book captured my imagination and I had every intention of following in their footsteps. I made several road trips into the southwest before 2004 when I finally set out to find the Grand Gallery.

Departing from a paved highway in central Utah, the dirt and gravel road to the trailhead for the gallery is about 25 miles long. I made the trip in February. It was so cold the night before I set out on the day-long hike that my gallon of milk turned into an icy slush overnight. The trail to the gallery descends from the tableland into the canyon on a very rough “road” dynamited in the 1950’s by uranium prospectors down a sandstone cliff to the canyon below. The hike takes half a day to the gallery and half a day back. I had it all to myself.

The pictographs cannot be precisely dated but are estimated to be thousands of years old, made by the Archaic peoples who preceded the Anasazi and more modern Pueblo people. Here are some photos taken on the way out to the trailhead and on the day of my hike. [Click on any image to enlarge, All photos ![]() Max Vollmer]

Max Vollmer]

The largest and strangest anthropomorphic figures are believed to be the work of shamans on their vision quests. The animal figures are thought to represent the game hunted by a later group of people. Fortunately, all the pictographs are now too high up on the wall to reach which gives them some protection from vandals. Erosion over the centuries has lowered the canyon floor.